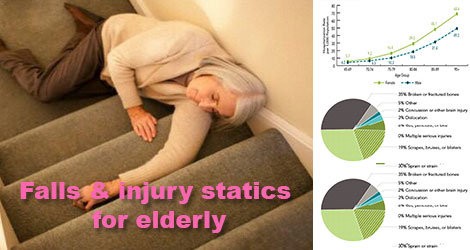

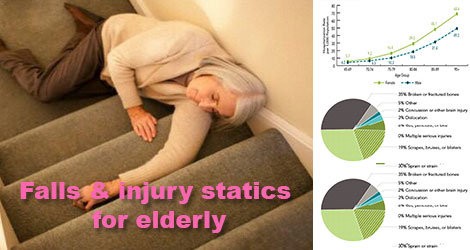

Several authors (Bonjour, Rapin et al., 1992; Delmi, Rapin et al., 1990) have suggested that undernutrition in the elderly may increase the risk of fractures during a fall. Others, using body measurement and laboratory data, have found a greater likelihood of falls in people with nutritional deficiency (Vellas, Conceicao et al., 1990). In a study done in Geneva (Rapin, Bruyère et al., 1985), it was found that at hospitalization, “(patients with) hip fractures were in a state of malnutrition in nearly 80% of the cases, dating to well before the fracture (8 months before)”. Undernutrition may lead to sarcopenia* and ensuing reduction in performance, coordination and movement, which may in turn favor the risk of falling (Evans, 1995; Vellas, Baumgartner et al., 1992; Baumgartner, Koehler et al., 1998; Baumgartner, Waters et al., 1999; Bertière, 2002). Furthermore, adequate muscle mass is important because it acts as a protective cushion, reducing the impact recieved by the bone during a fall (Dutta and Hadley, 1995; Bertière, 2002). Higher weight or weight gain during adulthood may thus provide a protective effect during falls, both in women and in men (Gordon and Huang, 1995). Inversely, falls may induce undernutrition due to their probable involvement in decreased mobility, loss of appetite and risk of needing assistance for eating.

Micronutrient deficiencies will appear when caloric intake is less than 1,500 kcal per day. Deficits are mainly in zinc (needed for the sense of taste), calcium, selenium (antioxidant) and vitamins (Ferry, Alix et al., 2002). Bone is the main reservoir for calcium and it is needed to maintain bone density as long as possible. Calcium levels are maintained through a system of regulation for which vitamin D plays a major role (Cormier, 2002). If calcium or vitamin deficiencies are present, the body maintains calcemia at the expense of bone tissue. Bones may thus become fragile, increasing the risk of fractures (Cormier, 2002). Also, vitamin D deficiencies are associated with muscle weakness and falls (Janssen, Samson and Verhaar, 2002; Pfeifer, Begerow and Minne, 2002). Although studies are few, falls seem to be associated also with deficiencies in vitamin B12 due to effects on proprioception* and B9 due to its role in cognitive impairment.

In some cases, undernutrition may unite with other factors and lead to an increased risk of falling, in particular for: – Chronic diseases (see “Age-related diseases”, p. 45): the frequency of falls is significantly higher in people with any chronic disease due to the nutritional deficiencies that they create (Gostynski, 1991). – Cognitive diseases: undernutrition and weight loss are frequent in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and weight loss increases as disease severity increases (Rivière, Lauque et al., 1998). – Reduced physical activity due to disease has a direct incidence on loss of muscle mass and fall-related fracture risks.

Alcohol abuse increases the risk of B12 and B9 vitamin deficiencies, which increases the risk of falls

There are several causes of undernutrition in the elderly. Beyond the consequences of aging on the sense of taste and nutritional assimilation, there are social and psychosocial factors that should not be neglected. These include loss of pleasure in eating, depression, financial difficulties, shopping problems, isolation, etc. Acute disease affects appetite while increasing dietary needs and is thus an important factor in undernutrition. When subjected to a quantitatively and qualitatively insufficient diet, the elderly patient becomes more vulnerable to disease aggression than a younger patient would be Regaining lost weight becomes difficult in the short interval between disease aggressions and, disease after disease, a state of undernutrition is established with resulting loss of muscle mass, possibly leading to an insufficiency in muscular reserve.

Acute alcohol consumption, meaning the abusive use of alcohol in a short period, is normally distinguished from chronic consumption, meaning its abuse over a long period. Generally, as alcohol consumption increases, so does the risk of negative consequences on the individual’s health and well-being. Alcohol abuse presents immediate and secondary risks, the latter being postponed and cumulative. Morbidity and mortality increase when alcohol consumption is globally greater than 21 servings per week for men (3 servings per day for daily drinkers) or 14 servings for women (2 servings per day). Consumption above these levels is habitually considered abusive. However for those 65 and over, these thresholds have been lowered due to an age-related decrease in alcohol tolerance. For this group, health risks increase when alcohol use exceeds 7 servings per week. Consensus exists among healthcare and road safety specialists on the health and accident risks associated with alcohol consumption, including in the elderly (WHO, 2002). However, despite an increasing number of studies on the subject, the impact of alcohol use on falls in the elderly is currently poorly understood.